Learning With Emotions

by Bernardo Bertolucci

I am not a Buddhist, but my relationship with Buddhism goes back a long way. When I was twenty-one years old, the great Italian writer Elsa Morante gave me a book to read on the life of the yogi Milarepa, and I was deeply impressed because behind the religious line of the story I experienced the presence of a great poet. In fact I felt more involved with the poet than the mystic. And the Buddhist experience has kept coming back to me in an intermittent way ever since.

In 1982 in Hollywood a friend invited me to a Tibetan Buddhist ceremony being held at his house in Brentwood, of all places, and I found myself sitting on the floor among a group of Tibetan lamas mixed with Los Angelenos. They were chanting parts of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. I received an initiation called Padmasambhava, named after the saint who first spread Buddhism in Tibet. The Tibetans were smiling, and that moment was contagious: I too was smiling, not just for the afternoon, but throughout the days that followed.

As you may imagine from this early experience, I couldn’t and didn’t want to make a movie about the life of the Buddha. What fascinated me was the challenge of confronting our present times with the thought of a man who lived twenty-five hundred years ago. That’s why the story of my film Little Buddha takes place today, and why out of the whole life of the Buddha I chose to show only a few episodes, which the Tibetan lama who is searching for the reincarnation of his teacher narrates to the American boy — just as a grandfather would tell a fairy tale to his grandchild.

At the beginning the film was full of lessons of Vajrayana Buddhism, but after months of sifting through my original material in the cutting room, what I hope remains in the movie is much more directly my desire to communicate to an audience the emotions that overwhelmed me when I first discovered Buddhism. For example, the very strong feeling I had on meeting an old Tibetan lama in Katmandu, sitting in front of him without the comfort of a common language. For in that moment there was an incredible sense of communion, an emotional understanding and communication which goes beyond duality. Looking at him was like looking into a mirror where I would see my face “morphing” into his face — there was no longer a teacher or a student but only one being.

Toward the end of my movie, the character of Lama Norbu recites the beginning of the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form”. What does this mean? Perhaps by the time I understand it, I won’t need to understand it. The emotion is what is matters. Not everyone can understand rationally, but almost everyone can understand through their emotions. And so I offer this foreword to Entering the Stream as an expression of my great respect for the teachings, and of my gratitude for the joy and the liberation that every Tibetan who collaborated on the film left in my heart.

September 1993

[Foreword to Entering the Stream: An Introduction to the Buddha and His Teachings, edited by Samuel Bercholz and Sherab Chödzin Kohn, Shambhala 1993]

B.B. (at one year an half...)

by Italo Spinelli

It must have been the early seventies when I saw Bernardo for the first time. I was at lunch with Elsa Morante at Babingtons in Piazza di Spagna, a Tea Room of refined clientele. We talked about Bertolucci and the huge success of Last Tango in Paris. Elsa reproached Bertolucci for taking advantage of the Hollywood star system with the presence of Marlon Brando. I was enthusiastic and totally overwhelmed by Last Tango, when, as if by magic, Bernardo materialized, entering Babingtons with a couple of friends. The appearance of this handsome young man with a broadly brimmed dark hat, left Elsa and me almost confused.

Bernardo approached our table, smiling and greeting Elsa seductively, Elsa introducing us in return. The two of them exchanged a few more jokes, then Bernardo joined another table with his friends. I could not take my eyes off this young, so adored, famous, beautiful and so irresistible director.

Those were years when in Rome you could still breathe – between Via dell’Oca, Via del Babuino, Piazza di Spagna and Piazza Navona – the air brimmed with ideas and passions, with civil commitment and enjoyment of life. The privileged protagonists who circulated in these spaces were Alberto Moravia, with his novels including The Conformist, which Bernardo ultimately turned into a cinematic masterpiece, Elsa Morante, who had already published House of Liars and Arturo’s Island and was writing La storia, and Pier Paolo Pasolini who had passed from literature to cinema with Accattone, a film in which Elsa appears in a small cameo. And Bernardo, in his early twenties, played his part as the assistant director of Pier Paolo’s first film. It was a literary and artistic world of intellectuals of bourgeois culture who met for lunch and dinner in a cultured, open, provincial and at the same time cosmopolitan Rome, which today has completely disappeared as if sunken into the abyss.

I had seen Bernardo’s first films, like his cinematographic debut The Grim Reaper, a Roman subject of Pasolini. Director of close-ups of religious, pictorial and anthropological inspiration, through Bernardo transformed into poetry cinema, with a constantly moving camera. Then came Parma, the sweetness of life Before the Revolution. Already before meeting him personally, for me he had become a cult director.

A second physical encounter with his cinema occurred coincidentally, again in Rome, in an evening of the end of the seventies, in Piazza Cavour, in the Prati district. Returning from the Bar della Pace, I saw Piazza Cavour incredibly illuminated. It was a spectacle of lights in proportions that I had never seen before. Entire facades of buildings, the Waldensian church, the palm trees and even the paved street were entirely flooded with light with reflections of daylight on the pavement of the square. I asked some people that were presumably of the film crew about what was happening and when they told me that it was filmmaking in progress, I was stunned and dazzled, and lingered, observing for a couple of hours. At some point, after a joyful agitation from the crew and orders given in Italian and English, a boy ran out of the cinema Adriano on the side of the square, into to the center of powerful spotlights with a crane mounted on a trolley that anticipated him.

When I saw Luna, the transition of the young protagonist at Piazza Cavour and the race out of the cinema Adriano, didn’t even last a minute, it was a transition. Yet that square illuminated by Storaro seemed to me like a majestic setting for an entire film and not one of the many sets that only run for a few seconds. That was when I realized how Bernardo could be an emperor even of Hollywood, with extraordinarily rich international sets, filled with his very own personal and inimitable creative freedom.

My acquaintanceship with Bernardo Bertolucci began twenty years ago. In fact, I had the continued privilege of sharing convivial moments, thoughts, emotions and visions with him. Bernardo went to the cinema almost every day for a long time. Then in the large and cozy living room of Bernardo and Clare’s home in Via della Lungara, which we called the Orson Welles room, we saw dozens of films together. I was always anxiously waiting to hear his opinion. He was always so faithful to the rule of Jean Renoir: “Don’t waste time talking badly about the films you hate. Talk about the films you love and share your pleasure with others instead”. He knew how to share about the images of a film that he loved, by making poetry. He was attentive to all details and ambiguities of the authors he loved: Renoir, Max Ophüls, Godard, Rossellini, John Ford, Antonioni, Douglas Sirk, Bergman, Chaplin, Howard Hawks, Sergio Leone, Kubrick, Satyajit Ray, Elia Kazan. Every shot of a movie that he loved could encompass his whole admiration. Strong in his love for cinema, he repeated that those who love are allowed everything. For Bernardo it was of primary importance to reinvent and rediscover cinema continually, and his sense and pleasure for discovery accompanied him always and everywhere. Bernardo was always sincere when he expressed himself with cinema, faithful to the intermittency of his heart. He especially loved the elements of time, the light, and the camera movements about cinema, and he was also certain that films needed to be made about the women and the men one loved.

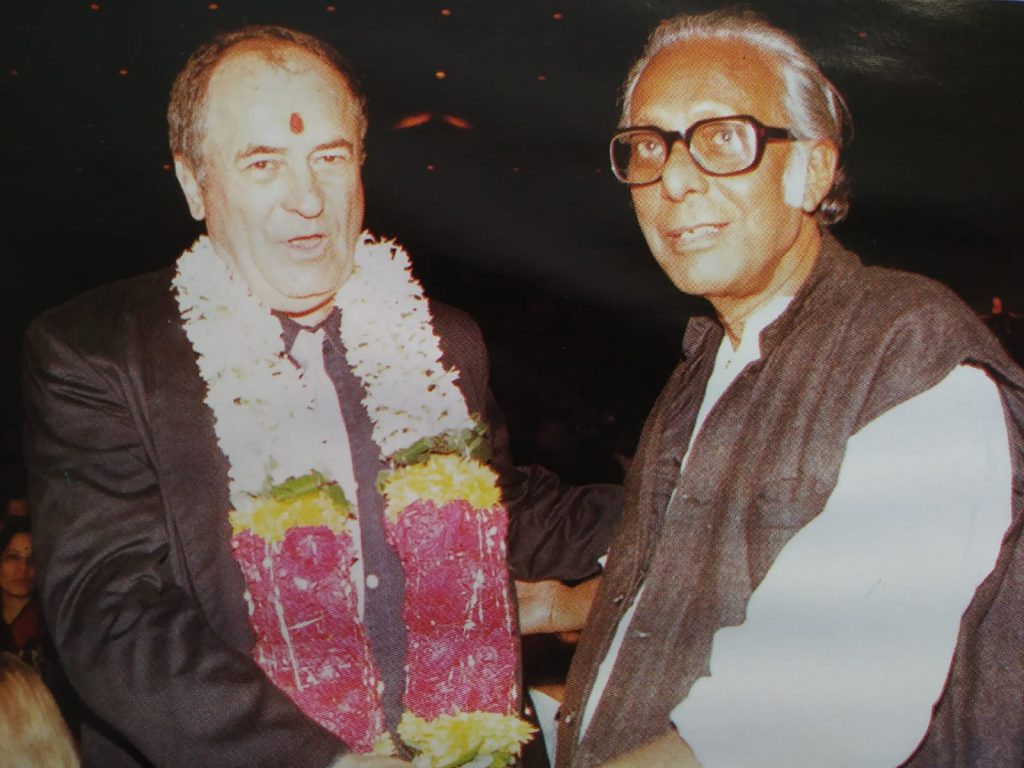

The inception of the Film Festival Asiatica in 2000, which happened thanks to Rossana Rummo who at the time was Director of the Cinema Department of the Ministry of Entertainment, gave Bernardo and me further opportunity to share ideas about a film festival in Rome that would bring rejuvenation to the capital. We wanted to present fascinating surprises that came from new cinemas: from Taiwan, Iran, Hong Kong and the Chinese independent cinema. In a pleasantness that only he knew how to offer, we chatted about the mutation that cinema was going through, with the new technologies and with emerging Asian cinema that experimented with new languages. When I returned from my incursions in Asia, my first thought was to show Bernardo what I had discovered. We were enthusiastic about some Tibetan, Indian, Turkish and Filipino film, about an Iranian documentary or the discovery of a new director such as Asghar Farhadi, or a new film by Hou Hsiao-hsien. I had the pleasure of introducing Bernardo to Hou Hsiao-hsien in India, on the occasion of a Festival in Hyderabad, where they were both invited as guests: Bernardo to receive a life achievement, and Hou Hsiao-hsien for his film Flowers of Shanghai. There were no translators but Bernardo was still able to praise the films he liked, persistent in trying to point out to Hou Hsiao-hsien that, in addition to the protagonists of the story who smoke opium, he also really appreciated the movement of the camera, which seemed to be under the effect of opium as well.

With how much enthusiasm he had appreciated the daring re-discovery in Tehran of Le Vent des Amoreux by Albert Lamorisse: a documentary of 1978 on Iran, which had disappeared with the revolution, and which I had fortunately recovered. In 2002 I had the privilege of following the genesis and the realization of the episode Ten Minutes Older, a 10-minute short film in black and white. It was produced by Wim Wenders and addressed to the theme of time, that Bernardo said, was “wonderful, metaphysical and, at last, terrible”. The opportunity to be on a set where everyone, without exception, expressed the happiness of working on a film for Bernardo, seemed to be part of a sort of collective falling in love.

The project was to be shot in Rajasthan, but for various reasons, including health, the short film was shot in an “indianized” Agro Pontino, an area of former swamps South East of Rome. This was because the cue was a kind of parable found in the Mahabharata. It was a story we had both already heard from Elsa Morante and that Bernardo had already mentioned in a sequence in Before the Revolution.

The Indian parable had become the story of a clandestine immigrant who finds a girl to marry, works at a service station and has children but in the end everything is swept away. Bernardo said that unfortunately all this was only a dream, given the destruction and obliteration of different cultures in the name of an alleged homologation that was spreading. The way we shared, however, remained the same. Falling in love with cultures, getting closer to cultures that were different from our own. “Instead of striving to erase them or destroy them in the name of an alleged homologation, we must try in every way to cultivate them, allowing them to fully express themselves”.

At the second edition of Asiatica, at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in 2001, Bernardo decided to participate, not only by meeting young Asian directors, but by blessing us a with a magnificent 8-minute short film of his site inspections made in China for The Last Emperor. It was shot by himself, in 1985, and was entitled Video Cartolina dalla Cina (video postcard from China). He called it “the little ant”, that he wanted to give to us as a gift to contribute to that edition.

His friendliness was endless. The welcoming generosity with which he knew how to entertain his friends, talking about politics, characters and books, telling stories, discussing sexuality, music and, above all, cinema. After dinners at his home he sent you home to sleep with a kind of happy awareness that you were going to wake up in a different world.

An awakening in the future, where, if it was right to rebel in the past, it will be even more so today.

“I left the ending ambiguous, because that’s what life is.” B.B.