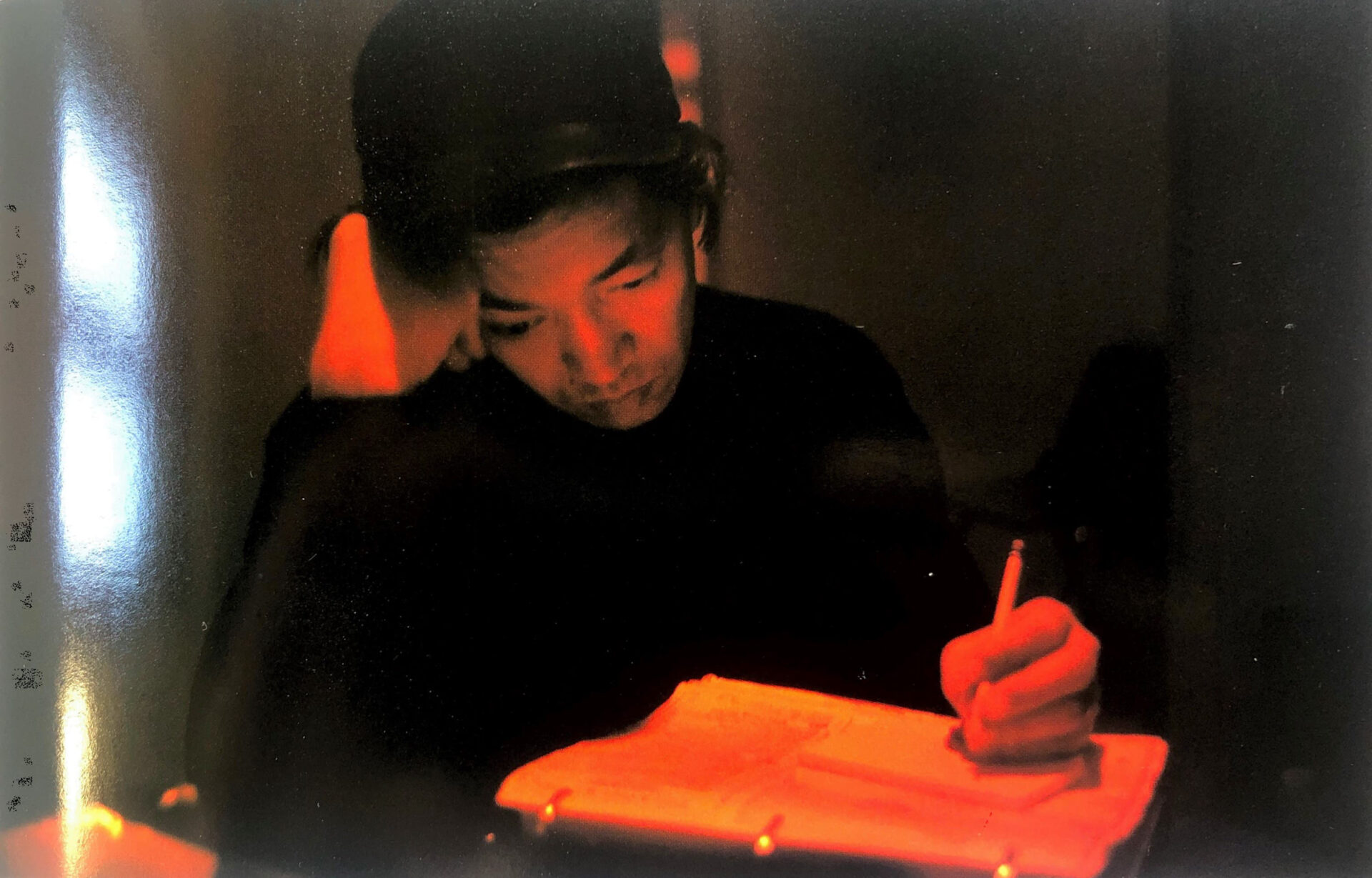

Sakamoto: "Per la morte di Bertolucci

mi sono seduto al piano e

ho scritto per lui"

Il 28 marzo scorso è scomparso nella sua città natale, Tokyo, Ryūichi Sakamoto, grande musicista contemporaneo, tra i pionieri della fusione tra la musica etnica orientale e le sonorità elettroniche occidentali, autore anche di indimenticabili colonne sonore per il cinema, da Furyo di Oshima a tre capolavori firmati dal Maestro Bertolucci, L’ultimo Imperatore, Il piccolo Buddha e Il tè nel deserto.

Nel 2019 il grande compositore giapponese, premio Oscar per la colonna sonora proprio dell’Ultimo Imperatore, venne in Italia per un’installazione, un concerto con Alva Noto e un film a lui dedicato nell’ambito del Festival Romaeuropa. In questa occasione, Luca Valtorta lo intervistò per Repubblica; durante l’intervista, Sakamoto parlò con ammirazione e affetto di Bertolucci:

“Sono proprio un maniaco dell’opera di Bernardo. La mattina in cui ho appreso della sua morte ho avuto come una sorta di illuminazione, come un’ispirazione: è come se la forza della sua arte mi avesse accarezzato ancora una volta. Ho sentito l’impulso di sedermi al pianoforte e di comporre un brano che ho registrato e mandato a Clare, la moglie di Bertolucci, affinché questo breve video potesse essere utilizzato e proiettato per la cerimonia commemorativa in suo onore”.

Lo suonerà?

“È la prima volta che vengo a Roma dalla sua morte. Ho scritto quel pezzo pensando a lui e non posso non suonarlo. Bernardo ha rappresentato qualcosa di davvero importante per me, per la mia vita”.

https://vimeo.com/357039424

A legare Bertolucci e Sakamoto, una lunga relazione professionale e personale, la passione per il cinema e per la musica. A parlare del suo amore per l’arte dei suoni è lo stesso Bernardo, in un’intervista realizzata nel 1987 dallo stesso Sakamoto (originariamente pubblicata in giapponese in A Picture Book of The Last Emperor):

RS: “I’d like to ask you about music, like how music has changed since your childhood…”

BB: “I started directing when I was still very young, but I was a poet even before that. It was simply because my father was a poet. Children like to imitate their fathers, you know. Then, I published a collection of my poems at 20. Looking at these poems that had taken their shapes, I felt like I was stealing something from my father, and I thought that poetry was not my realm. To tell the truth, I had always loved cinema so deeply that you could even call me a cinema fanatic. I made my first film The Grim Reaper at 21 in 1962, whence I realized that I wanted to use the camera in the same way as I used the pen. I believe that, compared to theatre, cinema is more like poetry or music. Theatre is simply made up of words.

Back to your question, now let’s talk about the evolution of music in my films first. Music has always been very vital to me. To an extent, it is musical films that I always wanted to make. In other words, my dream was to direct a musical without actual music, a musical where the image itself is the music. Maybe that’s why my camera moves so much- there is a musical approach to it. All the movements I love are organized and calculated like a rhythm- scherzo, adagio, andante, presto…

My second film [Before the Revolution] features Gino Paoli, an Italian cantautore from the 60s. He was writing really good songs at that time. He asked someone to do the arrangements, a young man I didn’t know then, a novice film composer whose name was Ennio Morricone. So the ’64 film was scored by these two, and Morricone by then was already the Morricone we know today. Yes, that was my first collaboration with Morricone. I worked with him before anyone else, even earlier than Sergio Leone.

Morricone and I continued to work together on the following films [Partner and Once Upon a Time in the West] I made in 1968. Then I made The Conformist and The Spider’s Stratagem, in which I used real film scores as well as Schönberg’s music, which I felt was very cinematic. I think that Hollywood film composers in the 30s and 40s listened to Schönberg a lot. We couldn’t commission a Hollywood composer, so we used the original, which was more interesting.

The Conformist is about the 1930s, so I appointed the French composer Georges Delerue, who is slightly elder than Morricone. The next film was Last Tango in Paris. The music was composed by Gato Barbieri, an Argentinean avant-garde tango composer. His music was, in fact, the only real tango element in that film. Because “Tango” was a kind of metaphorical title – the title came to me before the film. I wanted something that was connected to the real thing. So I asked Gato to do it.

Next is 1900. This is an Italian saga, an epic. At that time I really wanted a composer with an Italian touch. I wanted someone who could take the Italian musical tradition – folk songs, military songs, Verdi – and rework it into something new. Speaking of that, some of your songs remind me of the scores of 1900″.